On Writing Beyond Dominance

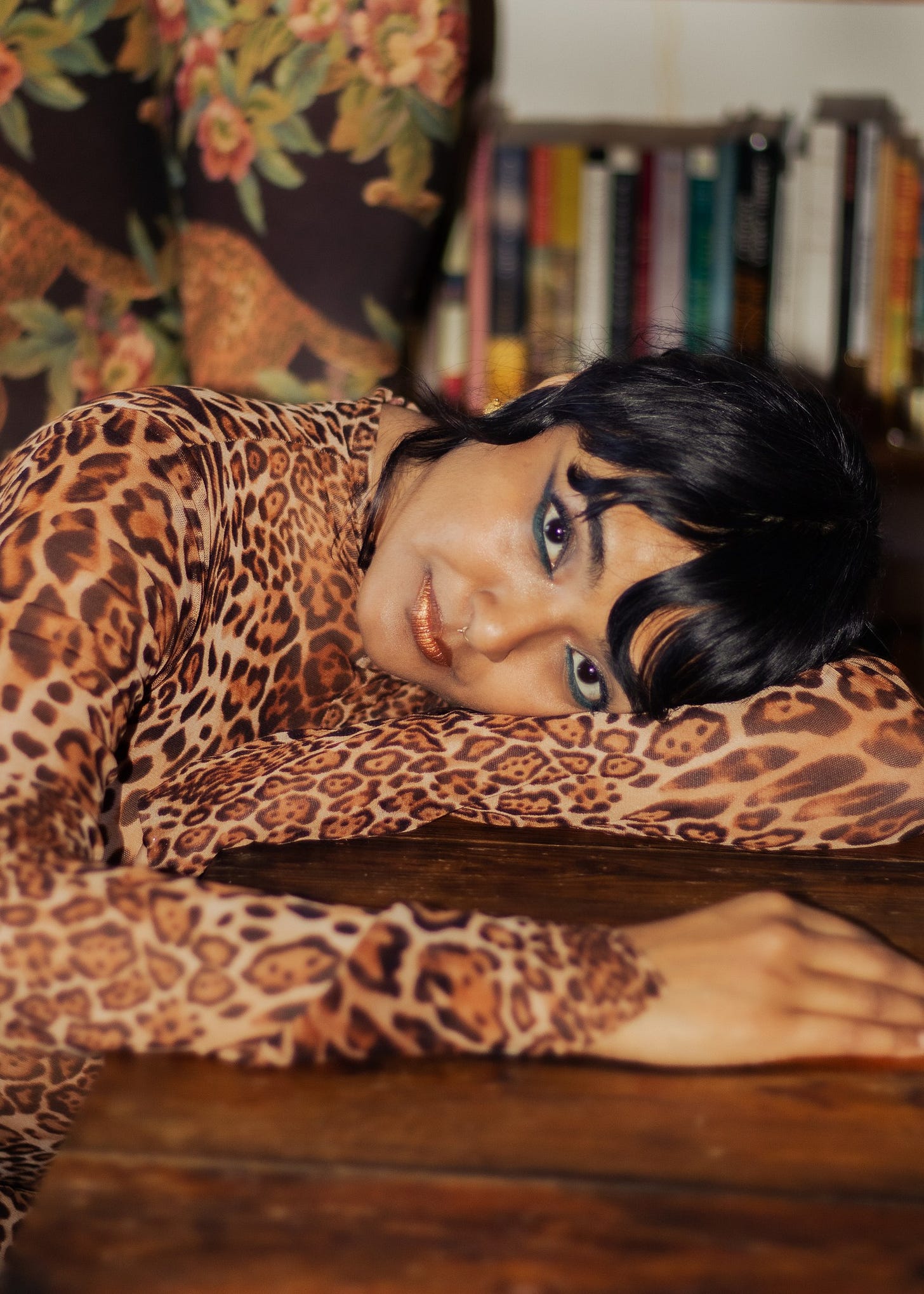

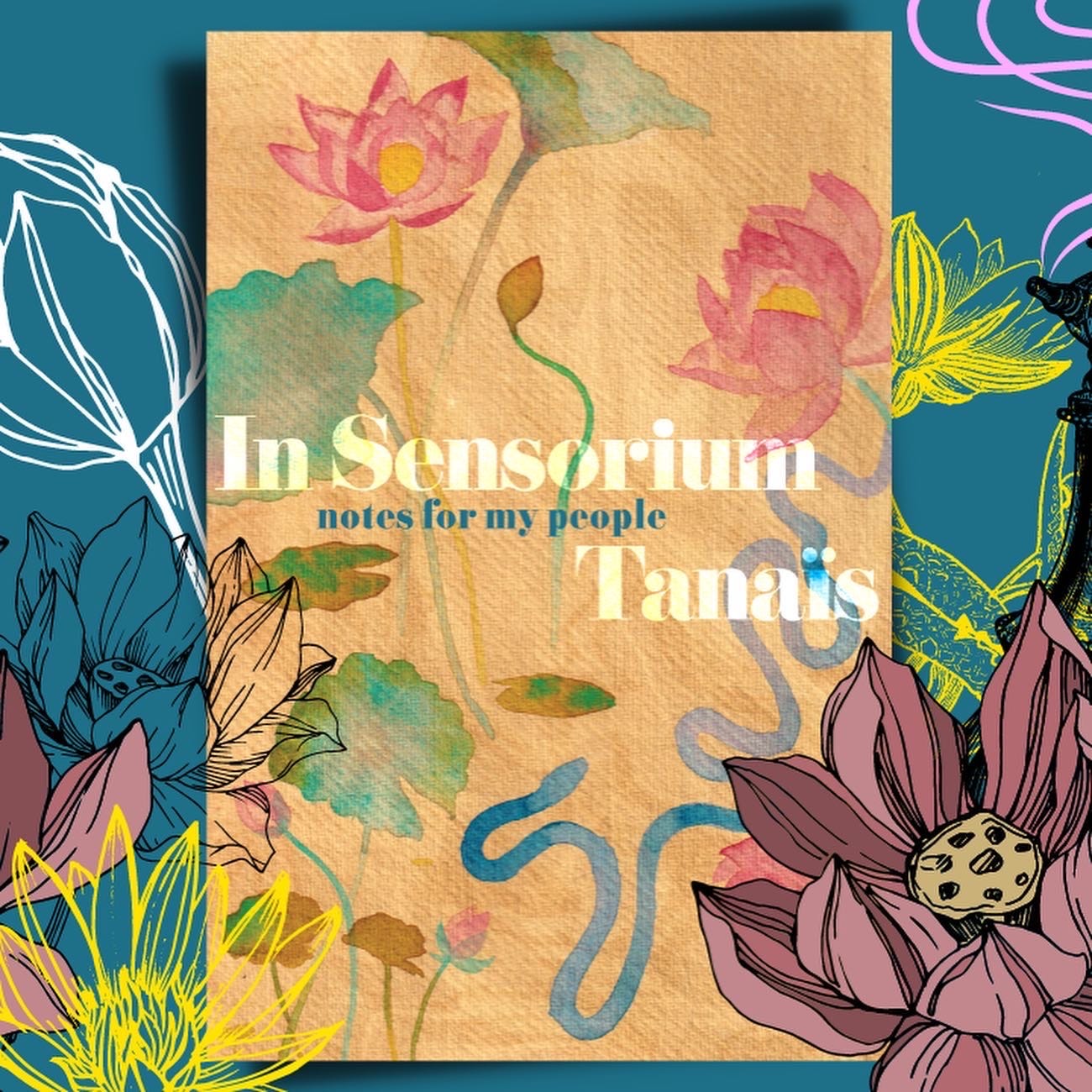

Thoughts on releasing In Sensorium: Notes For My People 2022. The Femme and the Fragrant. Solidarity. Stealers of Joy. Kindred Spirits. The Strike Wave. Respect. Embracing the Unknown. Writing Free.

Dear Ones,

Last night, in my Solstice meditation, I felt gratitude for everything that’s happened in the last ten months, and I felt so much sorrow. On ✨ 2/22/22 ✨ I published my nonfiction debut In Sensorium: Notes for My People. After arduous years of writing and releasing the work, in late October, my book went onto win the 2022 Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction, and a few weeks later, I found out that my book would not printed as a paperback by my publisher Harper Collins. Once the hardcovers sell out, In Sensorium will go out of print. (My audio book, which I recorded, lives on, forever, though.)

After all that work, that’s it.

What is “just business” to white people in media and publishing and in the arts at large, is everything that we artists of color take personally as hell. We pour our lives, hearts and health into our work. Sometimes, we take it so seriously, so desperately, because this might be the last book they let me write, so we work to the point of becoming sick. Heartbroken, after writing a book about the erasures of brown-skinned femme intellect by the dominant culture, here it is, happening to me—and for the last few weeks, I’ve been processing this insult.

It’s been a while since I’ve written to you, to be honest, lately, sitting down to write makes my body tense with anxiety and exhaustion.

Knowing that my work is actively being denied a future in more accessible form has forced me to confront feelings of failure amidst success. This is the time of year that writers brace themselves for the best-books-of-the-year lists—and it can feel shitty. I haven’t been tuning in much, because it’s not worth my energy. Let’s face it, the need to list and collect & categorize us is a central to how the dominant culture operates — the first, the best, the only is most interesting.

It’s not.

I’ve been hesitant to write about the path to In Sensorium in long form, because to be this vulnerable is fucking embarrassing. But that’s how I write my best work. When I have nothing to prove, or lose. I’ve proven myself. I’ve won. I’ve lost. I’ve chosen the path to write free.

So, I want to to share my pain, my joy, my petty, my rage, my heart.

Throughout this piece, I include some of words by fellow writers—mainly all queer people and femmes of color—whose writing about In Sensorium superseded anything I could have asked for, infinitely more intimate and interesting than anything I could expect from legacy media or white dominant culture reviewers. Often, these words moved me to tears.

That’s how it feels when you move from the void into the enveloping warmth of the sun. Illuminated, held.

“Everything they write, observe, mull over, is inherently spiritual. They make this association between divinity, scent, and identity as one entity, ebbing and flowing within one another…As an outsider…I am actively given the choice to confront what I don’t know.” Em Win, for Autostraddle, “Perfume Provides a Map of Memory and History in This Powerful Memoir”

The Femme and the Fragrant

In 2020, I started writing In Sensorium at the edge of my dining table, dealing with isolation, long-COVID, the death of my Nanu; losing my sense of smell, body dysmorphia after dramatic, unwanted weight loss; falling in love with an Indian artist, losing several friends because I no longer had the capacity to give in the ways I once had. I had never felt so sick in my life. I had not written a book in 6 years, not since my debut novel. I felt myself return to a state that I suppose is necessary for me to write: art-narcissist. (I will write more about this in the coming year.) I alienated people I loved with my need. I felt alienated by them, too. We wanted to be taken care of, but none of us had the capacity. I haven’t recovered many of those friendships yet, but every day, in my meditations, I send them love.

During this writing period, I deepened my marriage to Mojo by opening up conversations around non-monogamy, freedom, love, desire. Scary to tell the world, but over the year that I wrote the book, filling hundreds of pages of notebooks with notes, quotes, first, second and third drafts, after reading hundreds of articles and books, I knew that I had to write In Sensorium as vulnerable as possible. The book had come about almost as an accident, it was a side project tacked onto a novel that I did not sell: a speculative work about a mother-daughter separated in a time of global strife and reconnected through artificial intelligence in uncanny ways. (In 2018, ahead of its time, much?)

There is an electrifying power walking into a room as a brown-skinned, femme, beautiful, vocal person who makes direct eye contact and says what they think. It has taken me 40 years to find this power, one that is unnerving to white people, but also to your own people, because your body and the way you move rejects patriarchal control. Channeling my power, rather than trying to modify or minimize it, is where I found my voice as a writer again, in a new form for me, and not one I studied in an MFA: Non-fiction.

In Sensorium excavates the interconnected, intense, violent, painful and gorgeous histories of the South Asian diaspora, namely Bangladesh’s relationship to India and Pakistan, including the time before they were known as these countries, in a pre-partitioned South Asia. I wrote myself into eons of South Asian history, weaving parts of my life growing up in the American South, Midwest and New York. I reckoned with Bangladesh’s violent birth in 1971, a specter that all descendants carry, though we didn’t live it, as our parents did.

Perfume is a metaphor for borderlessness, syncretism, union, discord, transcendence and divine embodiment. Throughout human history, access to clean water, plumbing, social space and fragrant materials reiterated our caste and class status. Dividing the world by who is pure and polluted has upheld Brahmanical patriarchy, and justified white settler colonialism, genocide and slavery. This is hardly a revelation, but rather, it’s knowledge right under our noses. We are living in the final frontier of that colonial quest for spices and fragrant materials, gripped by climate change, mass migrations and mass death, animal extinction, and as ever—war.

“What this book seeks to do, then, is create a new historiography, inhabiting a feminine and queer perspective that shifts storytelling toward the writers, artists, and communities who have found themselves erased by dominant national narratives and who can’t be contained by any border, real or imagined.” Naib Mian, “The Hidden Politics of Smell,” The Nation

Unlearning Dominance & Practicing Solidarity

Writing is a powerful remedy for silence. I am a survivor and I’ve spent decades healing the part of me that felt silenced and violated. I never forget that my grandmothers married as children, never finished school, but here I am, writing free. To write ourselves and our foremothers into literature, to write in this canon of now, long denied brown-skinned femme people by dominant culture throughout much of history, is a profound privilege. I am protected enough to write free, I am loved, I am parented with love, I have written two published books without being harmed or imprisoned. I never, ever take this for granted.

Each day, I think about the tremendous courage of Kurdish and Iranian women as they fight for freedom, write for freedom, each day, as innocent people are arrested, imprisoned and executed by the Islamic State.

Writing lets me remember how I inhabit this body and mind as part of a vast lineage. In the same breath that I feel marginalized, or call myself a sexual assault survivor, I acknowledge my privilege: cisgender femme; Bengali Muslim in the Muslim majority context of Bangladesh; queer but married to a white passing man; paying mortgage in my family’s Brooklyn apartment; able-bodied, save for my eyesight. There is pain and suffering I have not known, have not yet known, but will one day, or cannot ever fully know, but compassion moves me. It is the reason I write. I write my work as an offering, to my readers, to the Universe, as a act of wresting back power, a way of soothing our collective hurt, as well as my own. I write for the beauty of language, even as that language is English, a language of dominance — knowing there are much more beautiful ways to write in languages I’ll never know. I write to give back love into our collective as deeply as I have known love.

There’s a line in Beyonce’s “Break My Soul” The Queens remix feat. Madonna. I listened to this song while dancing on MDMA, and this line resonated: Redirect all that anger / to me / Give it to me.

Privilege means holding the rage, letting it be redirected to you, so you can hold the burden, too. Those who don’t learn this lesson, never learn how to undo their patterns of domination. Holding rage is not the same as being abused—it is knowing how to honor how another has survived what you haven’t.

I want us to burn the patramyth, the lies of the record that have erased women & femmes & trans people who’ve built nations with their love and labor; who’ve been raped, killed and silenced in the name of these nations. Women & femmes & transpeople who’ve survived, whose protests, labors, intellects, styles, sexualities, art, beauty, rituals, prayers, songs, families—both chosen and blood—are the backbone of humanity.

And as an American Bangladeshi diaspora writer, to connect meaningfully with my Indian and Pakistani kin is a way to heal our historic fractures, with love, queerness and art.

As an artist, this is my inheritance, and my purpose. It’s what I live for.

You write of your own experience of rape, of objectification, of testing the bounds of your own sexuality with similar openness. But you also write of your love ceremony with Mojo, your partner, describing the love you two have built together. The bundling of cruelty, pain, and deep love together. I found respite in these pages that I did not know was seeking.” Nina Li Coomes, “How to Inhabit the Word,” Guernica, in a review written as a letter to me.

Stealers of Our Joy

I am loath to spend time hashing out how I feel harmed by whiteness, I hate writing about unmannered white women who have been rude to me, blatantly ignored my financial or emotional pain, often by simply never responding to me. By pretending I don’t exist because it’s too uncomfortable for them. I consider these people dead inside. The ones who work for their checks —it’s not personal, Tanaïs—gaslighting our reality, as if we are making a big deal out of nothing. This is the most traumatizing part of writing a book and publishing, that you have to deal with mostly straight white people treating your creation like their business.

In Sensorium was inherited by Rupert Murdoch’s publishing company Harper Collins, in their acquisition of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt & Mariner Books. Tracing our books path to an evil white man at the very top, knowing that somehow my work belongs to him, chills me to the bone. In the HBO Documentary, The Murdochs, we see how Rupert destroyed a print workers’ strike in England in 1986, by firing everyone and creating a secret production facility with modern computers versus old school printing machines. He crushed their fight, and some former workers still weep about the loss of dignity.

We live in obscenely rich white men’s virtual cages and playgrounds; using their apps all day, to sell ourselves, buying into their impoverished visions for society.

Originally, In Sensorium was to be published as a paperback, and I got paid a slim advance of $35,000 to write “a perfume book,” flippantly called so by nearly all the white editors who rejected the book on proposal. Some of their words are emblazoned in my memory:

“I just don’t see a book here.”

“I struggled to find footing and wished for a more clear, unifying framework to take us through these ideas.”

And so, I wrote a fucking perfume book that none of these white people could ever edit. For $35,000, divided by 2 years, 12 hours a day. $1.35 per hour.

Why is this a Bangladeshi woman and femme’s wage the world over?

Closer to publication, I sensed strange undertones in the air— trouble— when my original editor left Harper Collins. I lost my femme of color champion and ally, and from then onward, I felt every exchange with my “team” strained. I inherited a new young women of color editor, but still felt that I had no one to protect me besides my agent, who could only do so much from the outside.

I felt exhausted trying to translate my brown femme feminist worldview to mostly white people who did not understand my work at all.

Trouble: Explaining to Design why it’s wrong to add a white layer over an artists’ work, or cover it with a clownishly colorful text, ruining the raw beauty and brownness of the art. Such design choices whitewash brown and Black art to make it legible —however subconsciously so—to whiteness. Explaining to Marketing why it’s wrong to ship my hand-blended Pilgrimage perfume and book in a plastic bubble bag mailer, like a goddamn piece of trash. I advised them to do a printed box, as an invitation to a work of art. Explaining to Publicity why this sentence is the wrong introduction to the book: “Scent is frequently diminished as a lesser sense – a legacy of colonialists associating it with the “primitive”…scent is often associated with people of color.” Waiting for Accounting to send me a $3000 check—6 months late—for all the perfume packages we put together, with me fronting the cost on credit card, also known as not real money, but debt.

In each and every instance, my knowledge, and my taste level elevated the final beautiful product of my book. Yet, instead of feeling respected, or valued, I always felt like I was the one causing trouble.

On publication eve, my agent called me, frustrated and apologetic that not a single legacy media review—from the places all writers covet: The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic—awaited me on In Sensorium’s publication day.

At the time, I felt humiliated by how much I cared. How much it hurt. Even as much as I find white liberal media insufferable after the Trump years, I still fucking cared about those reviews that could make or break a book’s sales. I couldn’t sleep that night. There are a quarter million Bangladeshi people in New York City and not a single review for a New York City Bangladeshi femme author’s second book? My debut novel Bright Lines had not gotten those reviews either, even after I was a finalist for the First Novel Prize. The only author among us not to receive them. I told my agent that it was best to not let me know. On the day my book published, I wanted to feel joy for what I accomplished, not think about how no one cares.

My people did care, my people showered me with their photos, their unboxings and their texts and voice notes.

One obsessive thought came up later: Should I have let the white woman publicist do it her way? It’s hard to push thoughts like that away, but the answer remains:

No.

“Perfume is political, particularly for dark-skinned Dalit and Muslim femmes, who have been depicted by great Indian epics as “smelly, filthy and destructive.” To read In Sensorium is to be keenly alive to the need for beauty and joy as essential—as armour, particularly for those who are simultaneously invisibilised and hypervisible.” queer Bengali writer Riddhi Dastidar, for Vogue India:

Kindred Spirits

My first readers held In Sensorium with respect and love, they felt what I set out to do. I don’t share my work with many people outside of my agent and editor, besides my partner Mojo, my sister Promiti, I asked these three brilliant writers to read and blurb my book. Jenny Zhang, author of Sour Heart, and our late night talks nourished me during those early days of the pandemic. Imani Perry, who just won the National Book Award for her incredible book South to America and Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, the latter work even more meaningful to me when we went to see The Public Theater’s recent staging of A Raisin in the Sun together. We wept and marveled at the production, with a mostly Midwestern and Southern cast, including one of my best friends, Calvin Dutton (who appears in the last iconic episode of Atlanta!). Kiese Laymon, my first writing teacher at Vassar College, at this point we’ve known each other for more than 20 years, he knows how the original flame still burns brights, and you can see our virtual conversation hosted by Skylight Books as a testament to our writerly love and bond. When he was awarded a MacArthur Grant for his genius heart-mind, I cried, overcome with emotion. He deserves everything. Everything.

On February 25, I released In Sensorium at the Strand Bookstore with my friend the poet Megan Fernandes, author of Good Boys. Megan encouraged me to sing a few verses from a Bengali song “Megh Thom Thom Kore” by Bhupen Hazarika, “The clouds are thunderous / and no one is here” a melancholy song that my Bajan used to sing, which always made me cry. Afterward, everyone danced until dawn at The Sultan Room in Brooklyn. A few weeks later, I did an interactive reading and scent event at the Brooklyn Museum, in conversation with my Bengali girl Samhita Mukhopadhyay, author of the forthcoming The Myth of Making It. These events were warm, intimate, sold out in the dead of NYC winter—everyone who came craved the conversation and connection and perfumes. After so much time in isolation and cold, we dreamt about being outside in nature, in the forest, inhaling the the matí, the scent of rain on earth, and sacred flowers scattered on a river. Perfume, as a psychic connection between diaspora and desh.

“We had actually met once before, but as they write, “Sometimes powerful femme energy intimidates, and you want to run from what arises in its presence.” That night, we didn’t run. Instead, we talked late into the night about where our experiences were shared and where they were fractured.” Samhita Mukhopadhyay (above) The Cut, “Reclaiming Myself Through Scent”

Nine months later, on October 27, 2022, from the virtual comfort of a Zoom room, I dressed up in a little black dress by indie Indian brand Gundi Studios, wore my wedding gold, nath nose chain, earrings, red lipstick and a medical boot for my sprained foot.

“Is this too much?” I asked Mojo, as he handed me a Paloma.

“Babe, never apologize for your culture,” Mojo said, gently. “You look beautiful.”

How wondrous, and utterly unexpected, then, after all this, for In Sensorium to receive the tremendous affirmation: “seductive, vital, incomparable,” as I was awarded a literary prize in “overwhelming accordance” by a quartet of judges who believed in my vision, language and the scope of this book. The $50K endowed by Herb Simon (a wealthy white businessman who owns the Indiana Pacers, Kirkus Reviews and lots of real estate) allowed me to pay off part of the massive debts I’ve incurred from investing in my perfume and beauty house, thus letting me sustain my livelihood as an artist, as well as the livelihoods of the artists who worked with me this year.

The Strike Wave

My exquisite joy and sense of triumph lasted about a couple weeks. I had sensed trouble, again, first when Harper Books refused to fly me out for the ceremony, but then when they failed to post on the Instagram main—my primary way of reaching my readers—

I knew Harper Collins didn’t give a shit about me.

How ridiculous to think in the afterglow of the award, I could trust these people. People who didn’t even respond to me when I emailed. How naïve that I didn’t expect In Sensorium to become casualty of pure white supremacist capitalism—your book is not a bestseller and not worth more investment—a diss that hurt me to the core. Immobilized me for days. I spiraled. What more did I have to do, how much more did I have to prove of myself, how much did I have to nearly die trying, to make a publisher care enough to invest in my future? When would my work ever warrant protection?

We are never suffering alone. On November 10, 2022, Harper Collins workers began their strike.

The trouble is very, very real. And the dominant culture does not protect us.

It is Day 32 of the Harper Collins Union strike. Their demands are simple: they want a livable wage & benefits that make it possible for them to do what they love. ($5K more per worker, which Rupert Murdoch’s empire has more than enough to give).

This is part of a historic strike wave across the U.S. revealing the unsustainable labor and economic practices of dominant culture arts and education institutions, which can’t be ignored. Culture workers are revolting against unlivable pay and untenable expectations. Academic workers have been on strike at the New School, NYU and continue to be on strike at the Universities of California. Being asked to live in New York City on $40k a year, when rents are $5K a month, is absurd and dehumanizing. Especially when the highest levels of management in these corporate, or bureaucratized nonprofit and university spaces are rich. I stand with the Asian American Writers’ Workshop Union, (you can sign the union’s Open Letter of Support here), as well as the Brooklyn Museum Union.

Assistants, adjuncts, graduate students, people of color, Black, Indigenous, queer, trans, disabled and immunocompromised people living in an era of normalized pandemic have no security or safety net in place. These institutions benefit from their unpaid labor, and there is no way that we can lose our greatest allies in publishing. These are the assistants and young editors of color who are devoted to our books, constantly translating our worth to all white teams. They deserve everything they need to live.

Respect is Scarier to Fight For than Respectability

No matter how excellent, how beautiful, how brilliant, how respectable we are—in this matrix, we are not enough. By design. Under white supremacy, none of us will ever be enough. No matter how much we kiss white ass, center them in our stories, no matter how much we turn against ourselves and turn into buffoons, jesters, emotionally dead documenters of modern consumerism, purveyors of hypnotic prose detailing the sex lives of amorous, colonized main characters — we are not enough if we don’t make white capitalists their money. If we are not a return on their investment, as impoverished as the investment is, we are worthless.

That smiling, bespectacled liberal white woman publicity or marketing director won’t vouch for you if you don’t play the part of respectability, if you don’t let her do her job of making you palatable for white consumption, which matters more than actually treating you with the respect you deserve. Respect for our work means understanding that rage is a part of this work, and we are writing ourselves whole.

Whiteness erases, flattens, seeks conformity, believes in a false sense of superiority, and worst of all, whiteness is built on our pain.

When you’ve expanded your consciousness, when you have have self-love and self-respect, you know we can never be contained by dominant culture imagination. But this shit still hurts, and it will keep hurting, until white and upper caste people are as committed to destroying these systems of power as we are. Until they can hold your rage without being emotionally shattered by their own fragility. The constant state of being fucked with by mediocre people with socioeconomic privilege is a problem that terrorizes our mental health, makes us question our value, our future, and morphs into debilitating depression.

If the world around us is sick—how are we expected to be heal?

Embracing the Unknown

To be canonical is to permanent, long-lasting, evergreen. Perfume is ephemeral and fading, material-less. At the same time, it takes new life, an even stronger one in our memory. From Kyubin Kim’s brilliant Substack Silly Bus:

In my saddest moments, there is a longing—more of an ache— knowing I may never know this release from this system of dominance in my lifetime. Not until death—and sometimes I know what awaits my work after my physical death will be beyond whatever I can imagine. Whether obscurity or worship awaits—it remains Unknown—and I’m relieved. In Sensorium is a smoldering, slow burn, snaking its way through time and space, slowly discovered by my readers. I won’t sit here and be sad or humiliated by the fact I belong to a beautiful, misunderstood niche in American consciousness, despite how American I move my body, despite how American my voice sounds or the words I write. As capitalism demands: the more books I sell, one day I’ll be free to find a new publisher that actually cherishes this book—and me. I’ll have to write another book from scratch, start over with a new house. Maybe that will be enough. Enough to buy back the rights to that sweet, floppy paperback. Consider gifting In Sensorium: Notes For My People to someone you love, maybe I’ll get closer to that glorious day.

Happy New Year &

Infinite love and gratitude,

Tanaïs

i've been following your work for a while and was so excited when your book was published. it has been on my reading list ever since and as soon as i heard about the disgusting way harper treated you i bought 2 copies, one for me and one as a gift for my best friend. your work is important and you deserve so much better!!! i hope you have a more joyous and restful 2023 <3

This is absolutely infuriating to hear. Thank you for writing this post and exposing what the journey can look like underneath the image of "success" and glamour. Your book is a liberating triumph.