Late August is always suffused with longing: for the waning summer; for my Baj to live and grow ancient, his birthdays now a reminder that time comes for us all; longing for all the people I still love, but don’t know how to speak to anymore, longing to smoke a joint with them on my couch, or trek to the beach at Fort Tilden, eat Cape Cod potato chips, gossip, or kiss, our lips salted and sandy, swim, as raindrops hit the ocean surface, forming pores like skin, as sunlight and rain bend into rainbow; longing, for the freedom that still eludes us.

~

These thoughts will be a mere drop in this ocean of conversations we could have about South Asian diasporic love and discord—my book, In Sensorium: Notes for My People goes deeper than I’ll ever be able to go here. I move from foremothers to foundational learning to erasure to our future. We are a continuation. We are history, still unfurling.

I’m late to the spate of 75-years-since-Partition-1947-Independence pieces, perhaps that’s fitting, since my people’s liberation came 24 years later.

~

Six months ago, I launched my second book, a nonfiction memoir-lyric essay-hybrid text, In Sensorium: Notes For My People, at the legendary Strand Bookstore in New York City, with my friend and poet of East African Goan descent, Megan Fernandes (author of the collection Good Boys). Being in conversation with another South Asian diasporic artist, with Megan’s brilliant mind, put me at ease; sharing new, weird work is so damn vulnerable. I sang a Bengali song my Baj used to sing (he was stuck in Bangladesh, sick with you-know-what); and everyone smelled a perfume I composed called Matí, the scent of baked terracotta tiles that pregnant women in my Ma’s village would nibble on to quell pregnancy cravings, getting the minerals their body needed. Matí is an ode to our Hindu kin who ate matí, or dirt, of their ancestral land inEast Bengal, land they’d leave behind forever, to seek refuge in West Bengal, India, during the Liberation War of 1971.

Who are my people? People who are trying to heal lineages. Survivors. Sexy, irreverent, intellectual queers, femmes. My sisters. Hoes and hotheads. Anti-caste, anti-hegemony. Descendants of people who survived unimaginable trauma, created beautiful art, made families, both chosen and blood, lived to see futures. I want us to move beyond shared culture, language or citizenship as what binds us together. My people are my kindred who make art that moves me to my core.

As much as my writing is centered on Bangla femme people, whose art and freedom struggles I’ve taken to heart, we too, belong to a dominant culture. No violence that our people suffered justifies the continual sexual violence and murders of Indigenous Adivasi Christian, Buddhist and Dalit Hindu people who’ve lost their land or lives to Bengali Muslim settlers-colonizers. And this extends to our diasporic homelands, here, where we are settler-colonizers, too.

I never try to forget this in my work.

In the last few years, I’ve been immersed in a South Asian digital diaspora, more so than any other period in my life, which has mostly nourished me. Even from afar, we witness each other, we send each other affirmations, sometimes we party in real life. But if we let ahistorical aesthetics be our sole point of unity, we’ll eventually continue to perpetuate the fractures we’ve inherited.

~

Writing free—my pure, true thoughts, written without fear of political imprisonment or death—is immense privilege. And I decided, while writing my book, that I’m going to take up the space to do that, knowing that no institution, no money, no clout or community will keep me from my voice. The process of writing In Sensorium taught me that I have chosen to write free—I am literally writing this for free because who would publish this?—I can’t live otherwise.

Writing here—New York, USA, Waning Empire—is to speak within an echo chamber that won’t reverberate to the survivors, textile workers, non-English speakers and writers who inspired so much of this work. This is both a function of privilege living in the Global North, as much as it is about me, a writer, lacking access to a larger swathe of readers outside of the U.S. because who I write about is not considered universal enough to translate into other languages, for other markets—I’ve never published in India, nor the UK, home to millions of us—but do they see me as their people?

~

I’ve been writing this in my body for weeks, for months, really, since I published my book. Finding language, like a tongue working a piece of candy, trying to touch the softness inside. My tongue, sharpened by indignant bursts on the Internet, needed to get methodical, still, to find this language. In the evenings, I meditated at sunset by the East River, my body cloaked in its aquatic funk, a reminder that I’ve actually left my house, eyes half-open, violet and coral pools glittering on the surface of that filthy, gorgeous water. I stare at the vastness above and below, partitioned by this city I will never leave.

~

Writing in the Spectral Zenana

In Sensorium started to pour out of me after the death of my grandmother, who raised us for parts of our childhood, our portal to an old world, one that feel in my body, in the way I move, the way I look and stare and speak, the scents I love. Nanu married at 13, never finished school, lost her son, who died mysteriously in his sleep, read avidly in Bangla and English, smelled like coconut oil and paan and violet talcum power. My grandmother had a rage about her—a rage women and femmes have known for eons—your mind and body was meant for more than this cruel world has given you.

In Sensorium is a tantra, a word with sexual connotations in the West, but its literal definition is a loom, a warp, a weaving. Spiral thinking. I weave my own life into ancient texts, academic research, my knowledge of perfumery, and the survivor testimonials and writings of brown-skinned, Black and Indigenous and Muslim and Dalit and South Asian people.

During this period, I fell in love with an Indian artist, a complex relationship that unmoored both of us, besides complicating our lives, we felt electrically, powerfully drawn to each other. This love forced us to confront forbidden desire, and our inherited divisions, of caste, country, class. In each other’s presence, our attraction overpowered us, swooning with teenage fever as adults, for a spell, until a conflict would erupt and sever our connection, again, and again, until we felt the pull back toward each other. This love, intoxicating, painful, limited, infuriating, soul-stirring, pushed me to a new threshold of language, into other eras where people like us had fallen in love, too. I confronted a deep, potent well of rage inside me, as a 14-year-old survivor of sexual assault, harmed by a young Indian boy.

I wanted to heal young me.

One of the words that came to me early on in the writing process was patramyth, what I call the dominant culture’s record of history, the lies and omissions that protect the powerful. Perfume is the metaphor for the femmes written out of the patramyth, who are at the heart of my book: the ones both hated and worshipped by Brahmanical and Islamic and white American patriarchal cultures, the ones cast off as the smelly, ugly, dark-skinned whores, the beautiful and tantalizing and disposable, the sex workers whom I consider my intellectual and artistic foremothers. These are the femmes absorbed into nation-making, reduced by the patriarchy as mere bodies, aesthetics, entertainment, sexual, less than whole human beings.

~

Throughout South Asian history, Muslim and Dalit and Indigenous Adivasi femmes have long existed in the spectral zenana, perceived as backwards and oppressed by their men. Zenana, as in the inner chamber of a home, the sanctum where Muslim women were once relegated. Inside, they could only interact with their husbands, fathers, and sons. In the eras that Muslim women were separated from men in zenanas, draped in purdah, you wonder —why? How oppressive. But, if the society around you sanctioned that an upper caste Hindu widow— the women closest to the most powerful men— could be burned alive in a pyre, sent away to a penal colony, imprisoned for being a prostitute, then maybe hiding wasn’t the worst thing.

Would you want to be perceived?

Even today, dominant culture literature and history flattens the experience of brown-skinned Muslim femme people into one-dimensional patramyth, silencing us, or having upper caste people tell our stories, rendering our nuance and complexity and intellect invisible, stranding us in the spectral zenana.

~

My research uncovered a world of East Bengali women writer-foremothers who wrote ardently about their life experiences and liberation; including the first recorded autobiography Amar Jibon, or My Life —in 1876!— by Rassundari Devi, an upper caste Hindu woman from Pabna, my Baj’s hometown, which borders West Bengal; in the early 1900s, Khairunnessa Khatun, a Muslim educator who wrote about boycotting low-quality British food and textiles, calling for our people to flex their economic power in the struggle for Independence from the British; and the renowned Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, who led a Muslim women’s school and wrote one of the first feminist sci-fi short stories, Sultana’s Dream, which has been absorbed into Indian feminist historiography and inspired beautiful work, like artist Chitra Ganesh’s linocuts.

Begum Rokeya’s ancestral home is Rangpur, in present-day Bangladesh, a detail rarely mentioned by Indian feminists, but it’s meaningful for us, for it breaks the illusion that India’s feminist history is separate from ours.

Begum Rokeya faced a lot of criticism and outright hatred for her writing and fiery critiques of a sexist society, which denied Muslim women their education; she was childfree, worked herself to the bone, staying up late into the night, immersed in writing and making sure her her women’s school stayed open. In her time, the most powerful discourse—as in our time, right now, in the literary world and media today —belonged to Brahmins, the ones who imagined themselves as the inheritors of a Free India, the ones best suited for articulating nation-statehood, women’s rights, democracy, high culture and artistic imagination.

Our foremothers imagined a society where Muslim women moved though the world educated, economically secure and free from harm. They knew our vastness. They were ahead of their time.

The biographer Shamsunnahar Mahmud recalls a memory, six months before Begum Rokeya’s death by heart attack. Though her doctor advised her to stop working, and rest completely, she cried:

How can I rest, I do not even have the time to die?

~

Awakening, August 2003

Soul Summit at Fort Greene Park can feel like a spiritual experience—Black house and dance music resounding through those trees, brown-skinned bodies moving, tripping, sweating. Parties centered on Black joy and music are as much a sanctuary as they are sexy. I ran into an Indian musician friend who’d just played a set at DJ Rekha’s 25th anniversary of Basement Bhangra at Central Park Summerstage, in what appeared to be an ecstatic celebration of the classic New York City party.

Who could stop watching that unforgettable, gorgeous slow-motion video of Padma Lakshmi and Sarita Chowdhury on loop?

“You were like, the only brown person who wasn’t there,” he said.

“I know other Bangla folks who didn’t go,” I replied, bristling at his comment.

“If you say so.”

“I’m seeing all the desi folks I want to see here, the ones who dance at Soul Summit.” I felt defensive, but I wanted to soften the edge in my voice, because I genuinely felt happy to see him.

“Yeah, he said, smiling, “this is like the Venn diagram, of desis who love to dance and desis who love Black music.”

We laughed. It’s true, mostly South Asian dance parties, without the presence of any Black people or Black music, feels less joyous to me. Earlier, a close Bangladeshi friend admitted to me, My body politic won’t allow me to be there. We both remember those parties, years ago, bhangra dancing yes, but also remember being groped by drunk Indian dudes, the kind who would happily fuck a dark-skinned Bangladeshi femme, but never bring us home to Ma. Her comment struck me—we didn’t go because the way we’d always felt—like perpetual outsiders.

And for many of the people who feel right at home in that space, my parties and my writing alienate them in the exact same way.

~

The interaction with my musician friend took me back to the summer we first met, 2003, a life-altering August, summer of the New York City Blackout, nearly two years after 9/11. That week, in the city, I participated in a week-long summer intensive for South Asian youth called Youth Solidarity Summer, along with my sister Promiti and best friend at Vassar, Alicia, whose family are Indian Muslims from Kenya. Though I’d grown up close to a lot South Asians, especially Malayali Indian Christians and Bangladeshis of similar middle class backgrounds as my family, and collaborated with desi friends who acted in plays I wrote in college, I’d never been in an all-South Asian activist space. I’d visited Cuba with the Youth Communist League earlier that summer, and craved intellectual and political comrades.

YSS was a collective was formed in 1996 by South Asian progressives in response to the rise of Hindu right-wing fascism, which reached a fever pitch in February 2002, during the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat, India, helmed by today’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

No doubt, India’s “rise of fascism” has been a nonstop problem since the fight for India’s Independence. The people leading the workshops were mostly Indian diaspora, brilliant political organizers, activists, academics and artists, Bangladeshi,* mixed-race Dalit Indian, Sikh and Eelam Tamil folks in the mix. Even though I didn’t have the language for it then, I felt how those organizers were devoted to eradicating caste, or reckoning with their own peoples’ history of genocide.

I made a some friendships that lasted a few years, and kept a lifelong friend, Amita Swadhin, founder of Mirror Memoirs, an oral history project devoted to the healing of LQBTQI+ Black, Indigenous and POC survivors of child sexual abuse. They continue to create powerful, loving and radical queer unity that I craved so much as a young person.

~

Later that week, my sister, Alicia and I attended our first Black August concert. Incredible artists performed—Erykah Badu, Common, Dead Prez. Black August originated in 1979, in honor of incarcerated and murdered Black freedom fighters, and the concert was organized by the New Afrikan liberation organization the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, which continues to work today, toward reparations, freedom for political prisoners and education on Black revolutionary struggle.

I’ll never forget that when we told other desi participants that we went to Black August, they reacted with surprise that we’d gone to a Hiphop show. “Oh, wow. You guys went to that?”

That whirlwind of a week—they inundated us in liberation pedagogy, art-making, performing poetry at the Nuyorican Poets Café, recording a segment on a radio show, doing workshops around identity, power, privilege —and we survived the Blackout. The collective’s intention to get us youth to fight against Hindutva worked, here I am, still passionate, still processing.

But somehow, my sister, Alicia and I, Bangladeshi and Indian Kenyan femmes, left feeling a bit disassociated after the experience. We never felt fully comfortable, probably all the other South Asian youth felt that way, too. A bit triggered, but trying our best to be in communion. Desi, South Asians, Brown people, all terms meant to unify us, but when you look around, so often, everyone around you is Indian.

~

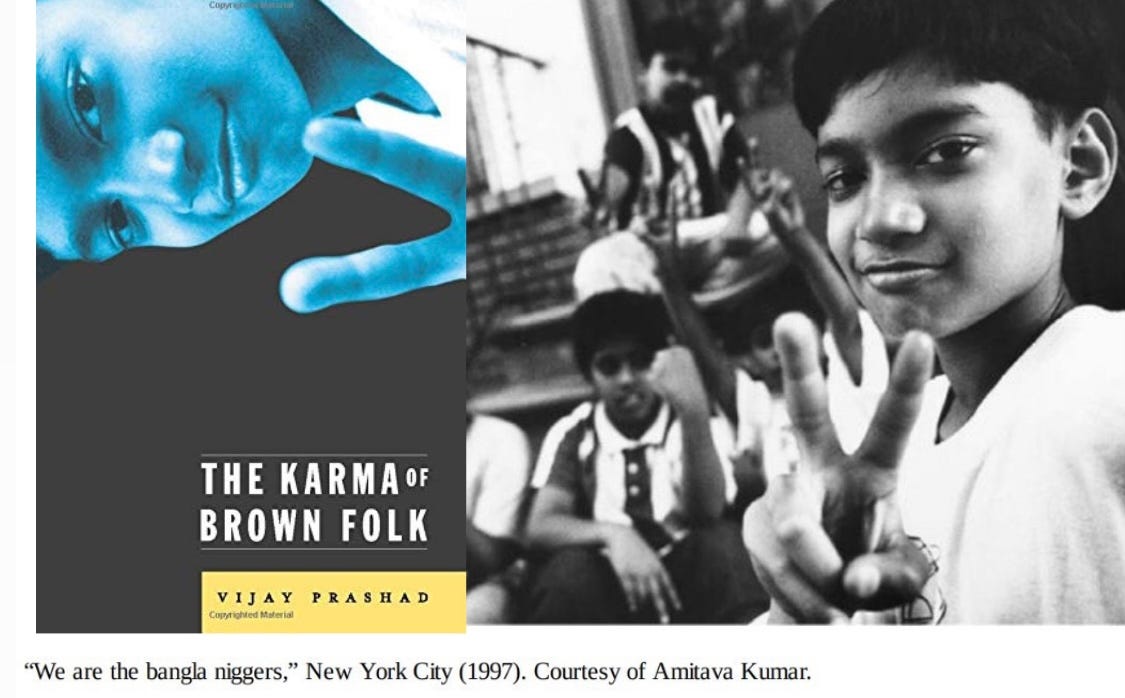

I had started to think of myself as desi, I trace this back Vijay Prashad’s book, The Karma of Brown Folk, seminal to my young consciousness. Inspired by W.E.B. DuBois’ 1938 lamentation that (upper caste) Indians felt more solidarity with Europe and desired to be Aryan, rather than align themselves with the African diaspora, Prashad’s call to South Asians: we need to be in solidarity with Black people.

Beautiful. But upon revisitation, the book felt utterly alienating. Like this sentence:

“Of course, Hip-Hop is definitely more of a medium of living and expression for people of color and I, being Indian, feel more like a person of color than white.”

I never noticed the light-skinned, upper caste privilege of that statement, as if there’s a choice for most of us whether we want to be a person of color or white. The Karma of Brown Folk’s cover drew me in immediately— the Bangladeshi youth, his coy expression, fingers in a peace sign, his skin cyanotype, Krishna blue.

Yet the only insight we have into his life is the caption under the full photograph inside the book:

(Note: I’ve left the caption as it appears in the edition I have, as well as the Kindle, and I’m sorry, because it’s jarring.)

I was so caught up in a dreamy narrative of desi and Black solidarity, again, I’d never noticed.

We are given nothing. Quotation marks imply that he’s the speaker. He has no name. No backstory. Nothing. It almost feels like it’s there to be provocative, like, see? These kids are so in solidarity they say the n-word. But I also can’t get over how it’s spelled out with the hard-ending, —gers versus —gas —there’s no way to know without sound, but I wonder if this is a misinterpretation by the non-American, Indian documenter. When the n-word is hurled as an epithet, for those of us born and raised in the States, we hear the the hard —ger and know how this word is meant to hurt and dehumanize. The choice to spell the word / hear the word this way implies a dehumanizing and a difference between the upper caste gaze and the subject of the photograph. Whereas —gas implies intimacy. We’ll never know.

The Bangladeshi-American city kids I knew growing up, who misappropriated the n-word, never theirs to say, often adopted AAVE to feel most at home with their Black friends, and in English.

And I’m pissed about the lowercase b in Bangla.

Prashad compels the reader to reject the model minority myth as South Asians, to find solidarity with Black liberation, but hardly acknowledges the lack of solidarity between South Asians, because of caste, color, country.

How are we supposed to trust you, if there’s not even solidarity with working-class, brown-skinned, Bangladeshi people, even as this boy’s face sold the book?

~

9/11 seismically shifted brownness within our lifetime, non-Muslim South Asians were being perceived as Muslim, as a threat, humiliated at airports, Sikh brothers gunned down for wearing their turban. I’ve felt this dread, since the 90s, during the Gulf War. When I was 7, my folks warned me: never tell them your last name is Islam, never tell white Christian people that you’re Muslim.

Passing as Indian, as Hindu, at different parts of my life, offered me a protection I didn’t inherently feel. I never do that anymore. But in 2006, when I moved to Delhi, a few years later, I often did so, just wearing a teep would do the trick, Bangladeshi Muslims wear a bindi more than most. I’d move through temples, tailor shops, one night stands, passing, to avoid judgment or hatred of strangers.

~

In 2015, one of the Indian-American facilitators from that summer reached out to me to do a reading for my debut novel, Bright Lines, at a city museum where she curated events. I was so thankful. This was before my book had gotten any press or award nominations, I was a debut author transitioning from nonprofit life, riddled with anxiety. When me and another author arrived for the reading, I realized the person who invited me wasn’t even at the museum, there were no signs, no staff knew about the event—not a single person showed up. I was beyond humiliated. We were ushered out in 30 minutes, as the staff had to prepare for a wedding.

You never forget when privileged people, who say they’re your people, act like you don’t matter. Who are rude to you, don’t show up for you, don’t hold your work up as important. You realize that solidarity is absolutely meaningless with people who never treat you with tenderness or love.

South Asia at 75

…Shaheed was staring at a maidan in which lady doctors were being bayoneted before they were raped, and raped again before they were shot. Above them and behind them, the cool while minaret of a mosque started blindly down. — Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children, the sole scene featuring East Bengali women, 1971.

On August 12, I was shocked to learn about the the brutal stabbing of Salman Rushdie by a young Islamic fundamentalist psycho. This horror unsettled all of us writers and artists who question, offend, reject and satirize. Rushdie remains one of the Indian writers who alighted my love of language. I spent the evening mourning the attack. I woke the next morning with a fresh, new patramyth by way of PEN International —

India at 75.

The 2022 PEN America Anthology India at 75, featured all Indian or Indian “affiliated” writers. (This according to one of the curators, whose family, ironically, were East Bengali refugees who settled in India, thus, her “affiliation.”)

Among them, writers I love, whose novels and essays I read, writers with whom I’ve had drinks, danced, wept, joined on panels and festivals, dropped acid. Friends, colleagues, nemeses, among them. Writers who are mostly savarna, Hindu, upper-caste writers, many of them venerated with awards, tenured university jobs, literary fame, wealth. I appreciated the inclusion of Indo-Caribbean writer Gaiutra Bahadur, author of Coolie Woman; Yashica Dutt, author of Coming Out as Dalit; and the oral historian Aanchal Malhotra, author of In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition, a powerful assemblage of interviews with descendants of Partition-impacted families in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

(I noticed immediately how Aanchal always names all three countries when speaking of Partition. It’s so rare. It means a lot.)

No writers of Pakistani or Bangladeshi descent appear in the anthology.

So, what do “Indian origins” mean, when we all have Indian origins?

Undoubtedly, the reasoning is for Indian diaspora writers to collectively speak truth to fascist power, against the Modi government’s terrifying repression of freedom of speech in India, the slow genocide of Indian Muslims, who’ve lived on the land forever, as well as migrant refugees from Bangladesh, too.

Our exclusion coupled with the timing of this anthology—on the 75th year of Independence, a date that is not only India’s—emits the same ethno-nationalist energy these writers imagine themselves fighting against.

Hindutva is not only deadly for Indians. Repression of journalists and the degrading freedom of expression is a problem in South Asia for all minorities and feminists and thinkers who question religion as an organizing principle of the nation.

India at 75 confirms that they do, in fact, see India’s struggles as singular, separate, disconnected from its neighbors, Bangladesh and Pakistan. These borders extend to exclusion of their fellow writers, who are Bangladeshi and Pakistani. And more heartbreaking for me, it reiterates—

We are not their people.

~

Each Partition tore our lands apart; from 1947 to 1971, when a mass exodus of mostly Hindu East Bengali people arrived as refugees in India during the War, eventually becoming Indians. While August 15 is celebrated as Independence Day for India and Pakistan, in Bangladesh it’s a national day of mourning the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, honored in the Bangladeshi patramyth as the founding father. Nationhood emerges out of blood. Unimaginable brutality, mass rape and death, permanent familial ruptures and religious separations—this is true for all of South Asia’s frontiers. Partition carved our ancestral land into bloody pieces.

So many of our ancestors fought for, and died for, Independence, but they would never be Indians.

Writers must stand against the fever pitch of fascism blazing across South Asia and our diaspora, against the incarceration of journalists, the bulldozing of Indian Muslim homes, against the murder of atheist or queer writers, against the murders of Dalit people in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, against the violent occupation of Kashmir, against the citizenship laws and concentration camps built to criminalize migrants who live in the borderlands between nations.

We are all inheritors of the same history.

South Asia at 75.

Say it out loud. Delicious assonance. Sounds sexy and powerful, no?

~

My experiences with the Pakistani diaspora hit a different raw nerve. Bangladeshi descendants learn the grim toll of 1971—numbers imprinted into us at a young age—a genocide of 3 million of our people; 400,000 birangona, the women and femmes raped; innumerable abortions and suicides; 10 million Hindu refugees left our homeland forever. Pure trauma. Inflicted by the Pakistan Army, which was mostly comprised of young men, poor, uneducated, far from home, a very different caste and class from the Pakistani artists I meet today, who don’t know much at all about this shared history, unless they’ve got uncles who were officers in the military.

Instances of feeling invisible when I’m supposed to be festive: at a literary event, a Pulitzer prize winner smiles and shakes my plus-one, white-passing, non-writer husband’s hand, and wordlessly looks through me, as if I were a pane of glass, not a fellow writer invited to the event. Or while watching the scene in Ms. Marvel, when Bangladesh FKA East Pakistan remains unnamed, and the Liberation War is vaguely referred to as a “civil war” —repeat after me: a violent military occupation cannot be a civil war— dimming the sheer joy of a Muslim girl superhero. Or meeting an artist at a party, awkward silence—he happens to be the grandson of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the Pakistani President who chose war, and ultimately our people’s mass death, rather than lose an election.

We’re not supposed to say these things, our collective culture is next-leveling as South Asians in America, trauma is a thing of the past, nothing we ourselves have lived through.

Across film, television, literature, music, we see representation of brown-skinned people, but of course, these projections will never be true for everyone.

“They’ve arrived, girl,” my friend Fariba jokes, and we laugh. It’s so true.

How do we arrive in a way that feels true, without selling out or constantly translating ourselves to white people? How do we stay true to ourselves without breaking unity? Why are we supposed to keep our hurt and history quiet, just to ensure others feel comfortable?

Rage, Love, Future

There are wounds I’ve yet to heal with other Bangladeshi Muslim femmes, fractures that happened because of anger, miscommunication, and letting each other go to choose ourselves. We’re intense and passionate people. In my heart, I love them, always, even though we felt harmed by each other. Even if we don’t reconcile, I want their work and art to thrive. These wounds cut deepest because we are each other’s people. If anything, the process of writing a book taught me how deeply toxic and narcissistic art-making can be, as well as how illness can make the mind-body interpret fissures as insurmountable.

~

I am still learning the shape of my rage, how it shapes me. As much as I know true love, as much as I seek to create beautiful work and treat people with warmth, rage in an unjust world doesn’t require justification. We live in a constant climate of rage against brown-skinned, Black and Indigenous, Muslim and Dalit oppressed-caste queer and trans people, women and femmes, this is the nature of dominant patriarchal culture.

Why should we trust anyone who doesn’t see how luminous and necessary we are?

Rage transmogrifies over a lifetime, we learn how to hold it, even feel this magic, for rage illuminates truth. May brown-skinned femmes rage when we’ve felt fucked over by someone with more power or physical strength. We evoke a response in others—aroused or uncomfortable or disgusted—undeniably, they feel you. We know what it’s like to stare back at eyes betwixt in that scary place between desire and violence.

To hold your rage is to love everything you are, no matter who underestimates you, who denies you, who despises you. You refuse to feel the smallness, the worthlessness, the erasure or judgment or violence of this world. This rage lives in your art, your relationships, your breakups, your sleep. But we know we can’t live like this, rage must be an impermanent state. You have to let it go. You have to let people love you.

As we continue to hold each other’s ancestral histories, we will confront rage. Inside this rage is pain, but the inner, inner heart of this rage is love, and longing for the freedom we all deserve.

Love,

Tanaïs

*Rest in Eternal Paradise, my old friend, Samuel Quiah. Please consider donating to support my comrade Sam’s wife and children as they try to build their lives after this terrible loss of a beautiful man.