Never Have I Ever...Belonged

On exclusion, feeling betrayed by your people, creating a brown archive, and Dalit queer and trans liberation.

Dear Ones,

It’s been a while since I’ve written you, and as usual, my timing is aligned with a cosmic transition, the Summer Solstice. Renewal, rebirth, stillness and reflection are on my mind. A lot is on my mind, actually. What started as another installment of my Dear Tanaïs advice column evolved into another piece that expands on the two profound questions that two of my readers asked me:

How do you work through feeling betrayed by your heritage and culture, while also feeling like this heritage is invalidated by the dominant culture?

and

Do you have any words of wisdom for a brown archivist in training?

I love these questions. Thank you for asking them, and here goes…

On Betrayal By Your Own

If you read my work, you know that I move through this life between love and rage. Rage is the fuel for my writing. My rage against injustice, against white supremacy and cisheteropatriarchal violence, against dominant culture erasure, these are the embers of rage I carry in my proverbial pocket, ready to alight the page. Moving through rage is an integral part of nonfiction writing practice. (All I want to do at the moment is write fiction, but I have some shit to say about the state of affairs; on South Asians making art, on what it means when we make art and do liberation work, and what it means when we feel betrayed by other South Asians.)

But those embers of rage, slowly collect into a burning, a burning in me that wants and craves love, a deep, critical love. I believe that profound, decolonized love is possible for all people. I have known this kind of deep, diasporic love that has healed wounds I’ve inherited as a Bangladeshi Muslim queer femme person, I yearn for reconciliation against the horrors of history, war, genocide and caste and gender-based violence. I want us to experience romantic love, sexual intimacy, deep, abiding, friendships, all unfettered by unnatural borders. I want us to fight for each other’s freedoms as vividly as we yearn for our own. I want us to speak to each other’s experiences, and through our actions, organizing, fundraising and celebration, reiterate: I hear you, I am with you, I will fight for you, I want to annihilate caste with you. I want us to acknowledge when we are privileged by class, caste, color, religion, ability, gender and sexuality in conversations and coalitions that require us to hold another’s rage and decenter our own. It’s not easy.

But I believe in us. I am trying to practice this in my own life, to always write and speak, even when I’m tired.

Tonight, several illustrious Indians, some of them my friends, fellow artists and journalists attended and performed at an event in New York City, with the rather dorky name Howdy Democracy, “a night of music, conversation and concern”—recalling the Texas summit called Howdy Modi, which welcomed the genocidal Indian Prime Minister on his 2019 visit to the U.S. Tonight’s event protests Biden hosting Modi’s current visit. At one point Modi had been denied a visa and banned from setting foot on U.S. soil for “severe violations of religious freedom.” The White House performs its usual imperial dance: Modi will be given the American head-of-state fanfare, rife with cheering crowds, marching soldiers, endless talks with heads of Indo-American think tanks, the Oval Office moment, private chef vegetarian dinners.

This is less about pointing my finger at individuals, or naming names, even though there are photos and easy Googling for you to do. They’re corny, for sure, and it’s all quite cringe. But I do know these artists care. They don’t want a fascist dictator in office. I know they work their asses off for every inch of their careers, and they work their asses off to organize these events in the name of freedom.

My critique is focused on them as a group, an Indian, caste-privileged group, and in turn, how they exclude those who they say are their kindred but don’t treat as such.

I'm one of those people.

It’s incredibly important to bring critical awareness to the dire situation in India, as “the world’s largest democracy” disintegrates into a fascist authoritarian state, endangering the lives of Indian Muslims, Dalits and Adivasi people, people of marginalized genders. As usual, the event seems to have excluded non-Indian artists and thinkers of South Asian descent, or artists from other borderland neighbor countries, like China, Bhutan, Nepal, or Myanmar, places where political repression and state-sponsored violence is hurting marginalized groups, too.

I wasn’t invited personally, perhaps because my political leanings and critiques of this kind of Indocentric group think are known by the organizers. There is a notable absence of Dalit thinkers or artists who actively organize and write in India and here in New York City.

Or maybe they don’t want us there.

*

To those asking: This is about the situation in India, why shouldn’t we focus on Indian diaspora artists? You don’t always include us in your events, why can’t this be for us?

Besides the fact that for all of our lives, we have been pinned to our Indian kin as one and the same, simply because of how we look, for many of us, when we say diaspora—we actually mean all of our people who trace their ancestry back to the South Asian subcontinent, to the land we now call India—

Our people lived on the frontiers to the East and West, our people are Adivasi dwellers in borderlands, the mountains and forests and hills, our people are from Kashmir, from Sri Lanka, from Tamil Eelam, our people are Girmit and Coolie and Fijian folks who traveled across oceans to labor on faraway plantations, to escape violence and oppression in their homeland, our people are descendants of survivors of domestic violence and rape, of widows escaped, our people were rejected for their religion, our people were rejected for being Dalit and outcaste.

Non-Indian South Asians and Dalit and Muslim Indians are descendants of people historically rejected by the dominant culture of what is now the nation-state India.

Let me be clear: the phrase our people is not to say that we are all the same people, or that we have the same histories and oppressions. In fact, our people have oppressed each other too, committed acts of brutality against each other, intermingled and shared histories. But I am speaking about today, in 2023, as we engage in liberation work. Like most Bangladeshi diasporic folks, I learned my parents’ experiences as young witnesses to the atrocities of war, acts of terror committed by Pakistani soldiers against Bangladeshis during the Liberation War of 1971, but today, I am building with a few Pakistani artists—like the two who encouraged me to write this piece, the poet and novelist Fatimah Asghar, author of the award winning brilliant novel, When We Were Sisters and the poetry collection If They Come For Us, and Misha Japanwala, artist whose solo show Beghairati Ki Nishaani: Traces of Shamelessness at Hannah Traore gallery is a radical, gorgeous and phenomenal act of resistance and an archive of femme bodies, a reminder that we belong to the earth.

I am building with South Asian diasporic queer and trans people, friends who want to learn from and heal with and love me, one of their Bangladeshi friends. I believe that we must find solidarity as kindred, as interconnected South Asians who’ve been shaped by inherited fractures that have carved our diaspora into scattered pieces, making it easier to continue cycles of oppression.

States divide people into separate groups, until they are smaller and smaller, until they disappear.

*

To me, as I’ve written before, it seems obvious that our voices together, as a diaspora, as South Asians, are more powerful. We can do more to illuminate the fascist rise not only in India, but in the whole world. Fascism is not a new threat to Indian democracy, or the Western Europe or the United States, fascism is a critical piece of the modern nation-state’s origin story—the rejection of all deep brown-skinned, caste-oppressed, Muslim and Dalit and Black and Indigenous people is a not a new phenomenon, it is a continuation of European colonial and Brahmanical patriarchal violence.

Over the years, I’ve been intimate social proximity to many of these Indian artists, filmmakers, media people and event organizers, these are people who I’ve considered friends, people I have loved, laughed with and fucked with, but, at the moment, I’ve distanced myself from them, because I’ve felt ignored as a writer, artist and thinker in these spaces. Not in the sense of individual love and appreciation, but when I am pretending to belong to this collective, the way I am cast away in the margins feels so acute. Why, I ask myself, why, should I keep putting myself into these artistic spaces, ones that uphold Indian hegemony and caste privilege, and never, ever truly uplift artists, like me, who are oppressed by these systems of caste, class and color dominance?

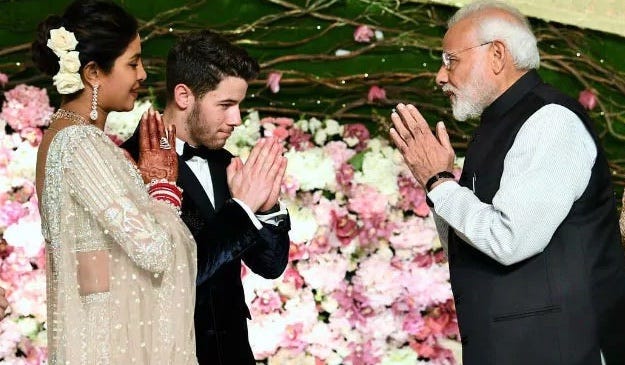

How does rage serve us when we feel betrayed? When we’re dealing with people who share our language, our skin tone, our nationality, but not our oppression? Are they our people? How do we build with savarna, caste-privileged Indian artists who perpetuate the erasure, exclusion and elitism that we associate with them? Don’t I have better things to write about with these precious hours than critiquing Indian wins? Wins include: visits to the White House, celebrating Diwali with Kamala Harris; party planning with Priyanka Chopra and friends at South Asian Excellence at the Oscars, or posing on the red carpet in India, at the Dior Show and the Ambani Cultural Center opening. Sure, I can set aside rage, but do I set aside the hard facts? Diwali, so often touted as “light overcoming darkness,” like Holi, is rooted in Brahmanical violence against Dalits; celebrating with Kamala Auntie means you’ve got to overlook her past criminalization of working class and Black families for youth truancy during her tenure as California’s attorney general. If you dig into the House of Dior you’ll find a Nazi niece, the billionaire Ambani clan, like all billionaires, have had their hands in Indian right-wing politics.

What these innocuous celebrations do, besides exclude, is revere a world view that actually harms Black, Indigenous, Muslim and Dalit people.

Despite the rise of beautiful documentaries centering the narratives of these groups, they’ve been directed and produced by teams that include Indian and Indian-American caste-privileged producers, like Summer of Soul (about the 1969 Harlem Culture Festival), Writing With Fire (about the Dalit news organization Khabar Lahariya), and The Elephant Whisperers (about an Adivasi couple who cares for elephants in the forests on the borderlands of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu) — we have to ask ourselves, how are these works actually helping the Black, Indigenous and Dalit and Muslim people who are centered in the work?

We have to ask: Why are these producers embracing Modi or Biden in strategic, contained moves to ensure their place in the imperial culture?

This working-within-the-system approach is how European colonization thrived, foreign powers forged alliances with the ruling class (in South Asia’s case, with upper castes, Brahmin bureaucrats, landowners and businessmen) ensuring their social privilege: money, property, power, prestige and safety, until, of course, they themselves wanted freedom from the white man.

Unimaginable horror made vast wealth and land ownership possible: theft, taxation, genocide, enslavement, rape, exploited labor, criminalization and the mass deaths of caste-oppressed people.

These are the grave betrayals we reckon with to this day.

*

(Confession: I binged and cringed while watching all of Indian Matchmaking — I would love for someone to bring a Bangladeshi, West Indian or Fijian woman home, and let’s see that Indian momma’s blood pressure rise!—and Mindy Kaling’s last season of Never Have I Ever. Disappointingly, Devi ends up with Ben and Princeton, an ending too basic and unbefitting this annoying but beautiful and charming young character played by the wondrous Maitreyi Ramakrishnan, our Eelam Tamil star. The obsessions with “excellence” and “Ivy League” and “white boy” reify a respectability politic central to white supremacist and Brahmanical patriarchal ideas of success. I, of course, would have preferred that Devi end the series on an acid trip with a cutie at a Seven Sisters College, but we knew Mindy wouldn’t —and couldn’t!— take us there!)

On Building a Brown Archive

Do you have any words of wisdom for a brown archivist in training?

As I work on my next essay collection—I know that I will devote a large section within the book to the this strange idea of “Brown” — capital B — this word brown so often used by South Asians to describe us as a monolith, implicitly excluding Black and Indigenous and brown-skinned people who aren’t South Asian. The overemphasis on Being Brown feels anti-Black, even as Black AAVE, music, politics and aesthetics are incorporated into a Brown aesthetic, but, as we see too often on social media, without proper credit. This performance of Brown, as a new collective consciousness—we are proud of ourselves, not ashamed, not colonized—has not yet transcended caste and color divides. When a “Brown” social space is occupied by a majority upper caste people, or light-skinned brown people, or straight cis brown people, it can feel just as suffocatingly exclusive as a predominantly white space for all the brown-skinned people who don’t feel they belong.

For many folks, an Instagram archive like @brownhistory is a huge source of knowledge, each post a preservation of image and history spanning centuries and lands. And yet, we have to wonder how helpful this archive is in certain instances that expose the disconnect of caste / color / region between the curator and the subject, like this, a post about the tragic murder of 20-year-old, intellectually disabled young man, Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, a Tamil Malaysian, who was found guilty and executed for smuggling 3 tablespoons of heroin into Singapore. Despite his economic hardships and vulnerability, he was not shown mercy by the State, and this story broke my heart when I learned the details from diasporic Tamil thinkers whom I admire. I found myself wondering alongside them, how this “brown archive” post could’ve been posted while Nagaenthran was still alive, to help possibly reach a critical mass of people in the diaspora to make a difference as he faced execution.

Dear Brown Archivist, my advice is that while you’re here, learning how to collect our histories from artifacts, records, heirlooms, photographs, maps, films, land deeds, textiles, jewelry, decor, diaries and certificates into a comprehensive brown archive, you learn to read that invisible ink between the lines, and you remember that you’re working for the liberation of all that’s been stolen, offering us, the living descendants, a way to make sense of the contexts within which our ancestors died and survived. Your work as a brown archivist is to imagine new methods of dismantling the patramyths that have long erased women, femmes, transmen, all marginalized genders from the record of history.

I want you to remember that our conversations must be a part of the archive.

While this was not recorded—sometimes necessary for safety reasons—this past Saturday, I went to a talk between Dalit Trans liberation worker and writer Grace Banu and founder of #DalitHistoryMonth, the Dalit feminist writer (mushroom forager!) Christina Dhanuja, moderated and put together by my Bangladeshi trans kin, the activist and writer Mikail Khan. The space felt intimate and familiar, like the queer theaters I used to put on off-off-Broadway plays in my twenties, this too, was a queer nightclub and event space, Purgatory, in my favorite part of deep Bushwick. There were about 35 people in attendance, all of us rapt at this conversation between two brilliant minds. Grace, a fantastic, moving storyteller, brought us to tears, and laughter, describing the heart-shattering extent of physical and psychological abuse she endured before finding her freedom, and how her trans mother and community helped support her quest to get an education, because she didn’t want to do sex work—and how they paid for school by selling sweet halwa! From Mikail’s gentle and probing questions, we were able to learn how Dalit trans people have fought for their right to education, work and their lives, in the face intense casteist violence, upheld by transphobic bio families, the police, places of employment and the legal systems, all which do everything to destroy a beautiful person for no other reason except they’ve decided they don’t belong on this planet in their full glory, as their full self.

Given all the anti-trans legislation being passed throughout the U.S. — I cannot overstate how sacred and how powerful it felt to be in the presence of Grace, Mikail and Christina as they spoke the truth about Dalit Trans liberation.

Part of Grace’s work in creating a Dalit queer and trans archive has been through her publishing imprint, Queer Publishing House. The vision is to center queer and trans authors, by letting them tell their own life-affirming stories, in their own words, in their own language.

Her conversation partner, Christina Dhanuja, asked us to complicate this idea that we must always be the ones to reckon with our “intergenerational trauma,” something we’ve all been thinking about, writing about, which is undoubtedly exhausting for a writer who wants the levity and space to collect flowers, to write their country beach house novel, and not always be asked to write with their ancestral lifeblood on the page.

“I want us to think about how savarna, caste-privileged women have now made fashionable jasmine flowers in their hair, turmeric face masks, henna, what have you, as part of their brand, but these were all disdained when it was us doing these things,” said Christina. “Why must I always think of my intergenerational trauma? Why don’t you think about what the harm your ancestors have done has done to you?”

This radical, courageous gathering of Dalit thinkers, in conversation with a trans Bangladeshi activist, is the kind of conversation across caste and country that we need for our new archive. We ended the talk by all joyously shouting, “Jai Bhim!” in honor of Babasaheb Ambedkar, the Dalit liberation fighter, jurist, architect of the Indian constitution. If you haven’t read his speech, The Annihilation of Caste, you can here. For more of Ambedkar’s writings and speeches, there are many preserved in India’s Ministry of External Affairs (strange that a great person most passionate about India’s internal affairs is relegated to this archive.) Here’s his Writings and Speeches Volume I but there are several more volumes if you search.

Part of the archivist’s work is being attuned to the patterns of what stories and material objects people collect and cherish, hints at what all humans want to preserve, proffering us, and the people of the future, a way to travel to our ancestors’ past.

*

One of the things that hurts most is how my book In Sensorium: Notes For My People, can’t reach my diaspora in the UK or in South Asia because it’s locked in North America, due to the nature of my book deal with Harper. There’s no paperback, there’s no foreign translations, there’s no international reach. If you try to buy the audio book in India, it will say it’s not available, and no publishers, neither in the UK, nor India, expressed interest in publishing the book, no, not even the South Asian / Indian editors. Maybe especially not them. For the way I’ve been ignored by these people, it is clear that the level of discomfort with discussions of caste in the literary world is still very high, as well as a general disinterest in Bangladeshi diasporic writers.

Yesterday, an Indian artist messaged me on Instagram to ask how they could obtain a more affordable copy of my book.

I had to let them know, sadly, it wasn’t possible to get a copy to them, for there is no paperback and no audiobook accessible in India. I lamented this fact publicly, and within a few minutes, a friend of mine, an Indian-American artist and sex worker, reached out and wrote me, “I want to sponsor a copy of this book.” Though she herself does not have a lot of money, she acknowledged her caste and country privilege, and wanted to do something to help, an act of love so huge and small at once, just to help my writing reach another. Within minutes, these two connected (and found a Kerala connection in the process!) The moment touched me so, so deeply. Here, two Indian people, diaspora and desh, connecting over my Bangla work, and all of us wanting to make our art to make this sweet, short life on Earth as beautiful as we can.

*

As always, this writing is free, and will always be free. You don’t have to pledge a subscription, but if you’ve made it to the end of this piece, please feel free to support my perfume & beauty creations at Studio Tanaïs, and use the code SOLSTICE20 for 20% off.

Love,

Tanaïs

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

I got goosebumps over and over reading this - thank you so much for your dedication to specificity of describing experience + the strength it takes to write about caste. it is an act of love!!!